I first read Lois Lowry’s The Giver in eighth grade, at which time the YA classic was already ten years old. I have not read it since, and I purposely did not re-read it in advance of watching Philip Noyce’s film adaptation for this review. That said, the book had on me, like it did on so many, a very strong impact. In many ways The Giver is the progenitor of the modern YA novel, and indeed it shares many of the characteristics of later works such as The Hunger Games.

My goal in not re-reading it, then, was to go in to this film with as little expectation as possible. I have a strong emotional memory of the book, but many of the specifics have long been lost on me. I therefore suspect that I enjoyed the film more than most, because despite my limited memory of the source material, I also suspect that the adaptation here is by and large one giant missed opportunity.

For whatever reason, one specific moment from the novel stands out in my memory: Jonas uses the word “starving” to indicate the degree of his hunger, and is scolded by an authority figure (precisely whom, I don’t remember)—after all, in this world no one is starving, and the Elders have worked very hard to ensure that. For Jonas to say that he is starving is therefore flippant, and totally disregards the effort that attained this utopia. While in the film, Katie Holmes’s Mother admonishes Jonas multiple times for his “precision of language,” this specific scene is entirely absent, along with almost any world-building that I certainly remember being in the book.

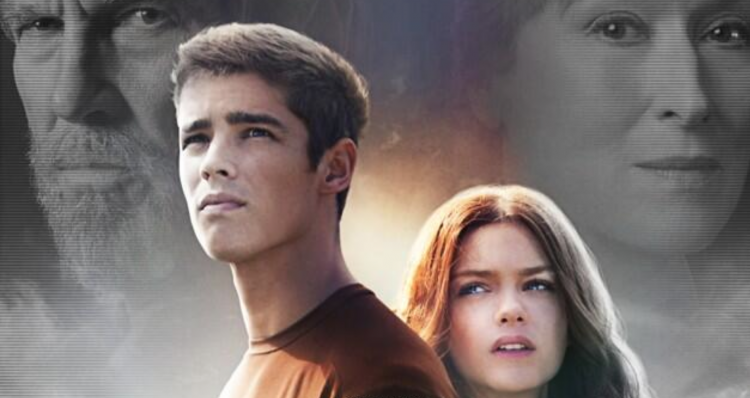

We are told constantly how perfect and idealized the world of The Giver is, but the screenplay doesn’t go to many lengths to actually demonstrate this bizarre society. We are launched right into Jonas’s “graduation,” with little sense of his friendship with Fiona (Odeya Rush) and Asher (Cameron Monaghan), or of his home life with Mother and Father (Alexander Skarsgård), or of how society functions in this world, beyond the most superficial level. From there we move too quickly into Jonas’s training, where the film then spends the bulk of its second act.

Fortunately the second act is also the film’s best, owing in large part to Jeff Bridges’ performance as the Giver. You see, Jonas is special among his peers, and is selected not for one the many standard occupations assigned to new adults, but instead is selected to be the “Receiver of Memory.” What this means is that, eventually, Jonas will be solely entrusted with the knowledge of human history, and therefore with the reason for the Community’s very strictly regulated society. So it’s down to the previous Receiver to train Jonas for this very important role. We learn along the way that there was a Receiver in between, Rosemary, who is played by Taylor Swift, but appears so briefly as to make very little impact on the plot or on the audience. Rosemary is a symbol, of the Giver’s grief, and of the cruelty of what Jonas is being asked to do—but she is not a character, and Swift is asked to do very little acting.

Jonas’ training is depicted through flashbacks, intercut with conversations between him and the Giver. Jeff Bridges and Brenton Thwaites (about whom more in a moment) have an easy chemistry here, and their mentor/learner relationship is a vivid and ultimately moving one. When toward the end of the film, the Giver tells Jonas that he loves him, we feel that, and so does Thwaites, who gives a remarkably understated reaction, mixing pride, relief, sadness, and admiration in a most beautiful way. This is the central relationship of the film, and so we need to spend as much time on as it as we do. In fact, I’d have liked to see much more of it.

Beyond Jonas’s slow discovery of the things that have been removed from society—colors, music, love, envy, war, violence—the plot of the film is rather thin, centering on an infant, Gabriel, who has been designated “uncertain”, meaning that he will not immediately be assigned to a family unit. What this really means, as we and Jonas eventually learn, is that Gabriel will be killed. This understandably is the last straw for Jonas, who leaves his training early and travels with Gabriel beyond what is called “the boundary of memory,” both to save the infants life, and to restore memory to all of society.

In other words, this is fairly typical, dystopian YA stuff—a young protagonist singled out from his peers, given responsibility undue his age, who rises to the challenge, uncovers misdeeds among the establishment, and rebels. It was revolutionary in 1993, but now it seems a pale imitation of The Hunger Games. That’s mainly because of the screenplay, which does not do nearly enough to explore the themes and emotions that the source material engages with. Bridges, along with Meryl Streep as the Chief Elder, lend the film an appropriate sense of gravity, but neither is able to save a script that is seemingly unwilling to challenge its audience with any truly tough ideas. There is an attempt here to boil the material down to a “love conquers all” sort of story, and that’s just weak. Given Bridges’s long involvement with this project and his reported passion for the novel, one wonders why more of that does not translate to the screen.

It’s a shame, too, because the movie is certainly competently made, and at times is truly beautiful. Philip Noyce has an elegant way of staging scenes, especially during the long middle section that is comprised mainly of Jonas and the Giver talking to each other. The film’s use of color, extremely important to the narrative, is nothing short of fantastic, as the lack or presence of color becomes narrative shorthand that is used to great effect, especially toward the film’s climax. Similarly, the flashes of memories that Jonas experiences benefit from the transition to the screen, as Noyce employs real-world history to demonstrate both humanity’s capacity for violence and our capacity for love and triumph over adversity. Marco Beltrami’s score is not particularly inventive, but it does a great job of underscoring the film’s most emotional scenes.

Which brings us to the rest of the acting. It’s standard of the YA film adaptation genre—because at this point it really is its own genre—to pepper the supporting cast with recognizable, talented adult actors, and that’s the case here as well. Bridges, Streep, Skarsgård, and Holmes each play their parts effectively, but none save Bridges have quite enough material to give the characters any dimension, despite their best efforts. But they’re only there to support the film’s true stars, typically a trio or more of teenagers (or approximations thereof).

Here, the film’s undoubted lead role is that of Jonas, played here by Brenton Thwaites, who is sure to become a household name sooner or later based on his striking good looks if nothing else. He carries the role admirably enough, but is essentially playing the same note, that of wide-eyed wonderment, throughout. It’s a good note, and appropriate enough to the character, but again, one wishes for a slightly deeper dive into the character. There are a few moments where Thwaites does excel however, mainly with Bridges as his scene partner. He’s also a gifted comedian—I would watch him make faces at babies all day long—but understandably is not given many opportunities to exercise that particular acting muscle here. Similarly, Rush and Monaghan’s characters have very specific narrative roles to fill, and beyond acting out those requirements, there is nothing else done with Fiona or Asher.

That’s really the problem with the whole film—it’s paint-by-numbers YA, when it should feel as revelatory and revolutionary as Lowry’s novel did, and still does. It’s difficult to know to what extent to fault the actors, to what extend to fault the script, and to what extent we should simply fault the Weinsteins. An examination of a utopian society that nonetheless murders babies who aren’t up to snuff is inherently fascinating—here it’s almost boring. And while the ending is mostly faithful to the novel as I recall it, the film doesn’t earn its ambiguity, especially as it also doesn’t make any sense. It achieves its emotional goal well enough, but why on earth should Jonas’s action have the effect it does? The best science fiction explains its technology, but here we’re asked to assume an awful lot. I’m not sure how Lowry handles this in the novel, and maybe it goes unexplained there as well, but here in the film, it’s one of those endings that works just until you give it even the slightest thought.

The Giver, as a novel, remains an essential treatise on the complexities of the world, and of growing up, of the importance of feelings even when they are bad or destructive. It is for many readers their first exposure to the idea that passion is a double-edged sword, but that to have either edge you must have both. It is impossible to eliminate the bad from this world, and in the attempt to do so, you risk becoming that bad yourself. The film gestures at all of these ideas, but it does so in the most streamlined, Hollywood-ized way possible, without giving the ideas proper weight or consideration, the way I know its source material does, even years after reading it.

The movie’s hovering around 28% on Rotten Tomatoes as I write this. It’s not as bad as all that. As a film, The Giver’s biggest crime is that it does not live up to the promise of its concept. That’s a pretty central failure, though, and so it spills out and poisons other aspects of the production, as well. You’ll undoubtedly enjoy it as you watch it, especially if you are nostalgic for the book, as even I am. But it will not stay with you for very long after you leave the theatre. Unlike a film like Catching Fire, which vastly improves upon and elevates its source material, The Giver stumbles, simplifying concepts that resist simplification, and making a very forgettable film as a result.

Michael Wampler is a graduate of The College of New Jersey, where he completed both B.A. and M.A. degrees in English literature. He currently lives and works in Princeton, NJ while he shops around his debut novel and slowly picks away at his second. Favorite shows include Weeds, Lost, Hannibal and Mad Men (among many more). When not watching or writing about television, he enjoys reading, going for runs, and building his record collection.