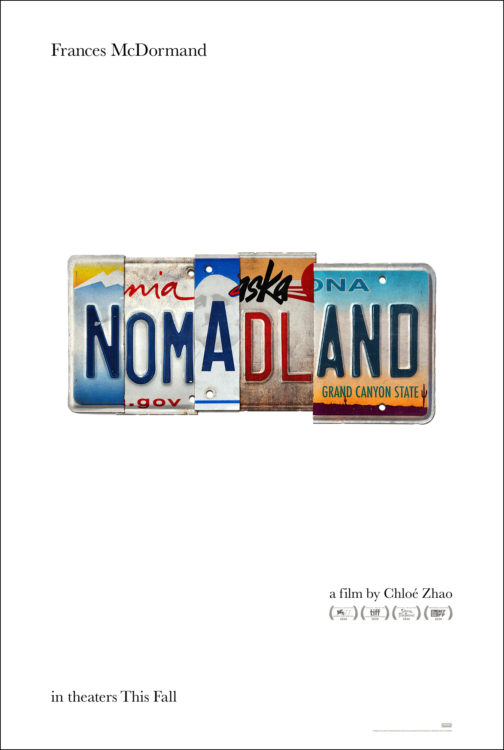

Nomadland follows a widow as she tours the west living out of her van with just her fellow nomads for help, company, and strength

Quick cut: Chloé Zhao makes Nomadland‘s melancholic but hopeful story of nomads traversing the American West a stunningly complex character study of life on the margins of society.

Chloé Zhao makes Nomadland‘s melancholic but hopeful story of nomads traversing the American West a stunningly complex character study of life on the margins of society.

![]()

It's often drilled into us from a young age to seek stability. Find a steady job, settle down with someone, buy a house, save your money. So, why do we leave? Why do we stay? What motivates us to keep moving forward—or keep retracing our steps? For the subjects of Chloé Zhao's new film Nomadland—which was the centerpiece selection at the 58th New York Film Festival—movement is life and staying still is something of a finality.

The film, which is adapted from the non-fiction book Nomadland: Surviving America in the Twenty-First Century, centers on Fern (two-time Oscar winner Frances McDormand), a former resident of a Nevada company town called Empire where both she and her late husband worked at a gypsum plant for decades. Following his passing and the collapse of the town after the plant's closure, Fern takes to the road living out of a van jumping from job to job and nomad settlement to nomad settlement. A “houseless” living as she says instead of homeless.

In each settlement, she often sees familiar faces of those she's met before on the road including Dave (David Strathairn), another nomad whose devotion to the lifestyle may be wavering, and a few other characters played by real-life nomads. However, there's rarely a moment to latch onto—but that doesn't make them unimportant. McDormand, whose greatest talent is to emote without saying a word, plays across these people and hears their stories. They divulge their reasons for moving—losing a loved one, making the most of their life, making the most of their death—which Fern absorbs with a quiet intensity as she evaluates her own reasons for being.

💌 Sign up for our weekly email newsletter with movie recommendations available to stream.

ADVERTISEMENT

Nomadland is quiet by design. Fern doesn't speak more than she has to, none of the characters do. It echoes their deep understanding of each other. They know little about each other, but what they do know is they're all wanderers and that is enough for them to bond together. We explore the small wonders of living on the go—how you use the bathroom, find a place to park for the night, keep warm—but what is more important is the wonders of deciding to live as a nomad in the first place.

The moment that soars Nomadland to greatness and gives Zhao her greatest argument to be the first woman of color to be nominated for Best Director at the Oscars belongs to a non-professional actor and real-life nomad named Swankie. Charlene Swankie, both the character and person, has a long history on the road. And in the film, she is one of the three mentors that helps Fern in her journey.

She recounts to her how she found herself on the road and what it means to her. The heartbreaking but hopeful monologue—I won't spoil its contents—tells us everything we need to know about being a nomad. It's what people have done for years to survive and for these people, it's no different. It casts a melancholy tone over the film, one underlined by Ludovico Einaudi's stunningly homegrown score and Joshua James Richards's nostalgic cinematography. Zhao doesn't chastise her characters for their choice, however, she doesn't shy away from the trade-offs.

However, it isn't just survival. There's joy in the experience. There's simple joys in every day of living an unattached life. Beneath the melancholy of it all there's something so primally joyous about watching this group of largely elderly folk enjoy each other's company around a campfire. It's almost the antithesis of Jim Jarmusch's Paterson. In that film, he finds the simple joys in routine and the places and people you see everyday. Nomadland flips it around and finds joy in the fleeting moments between destinations.

Underneath it all is the subtext of how the United States has largely failed the working class. The town where Fern lived with her husband, happily—as she works through in an Oscar-worthy monologue, was destroyed because of the 2008 financial crises. Her largely seasonal jobs are unstable and just enough to supplement the little income she receives from social security. Under those circumstances, being a nomad becomes a necessity.

However, as McDormand delivers in her signature deeply moving but opaque style of performing, it may have been a necessity, but it slowly morphed into a choice. Why participate in a system that isn't stacked in your favor? In this foreign universe of nomads, we learn why each person moves or stays. More importantly, though, we learn that it's never for the same reason—and none of those reasons are wrong.

Nomadland will be released on December 4, 2020.

ADVERTISEMENT

More movies, less problems

- Jordan Peele Unleashes the First Trailer for ‘HIM'

- ‘Sinners' is the best movie of the year | movie review

- Romantic sci-fi thriller ‘The Gorge' hits its mark | movie reivew

Hey! I'm Karl. You can find me on Twitter and Letterboxd. I'm also a Tomatometer-approved critic.

💌 Sign up for our weekly email newsletter with movie recommendations available to stream.

ADVERTISEMENT

💌 Sign up for our weekly email newsletter with movie recommendations available to stream.

ADVERTISEMENT

Hey, I'm Karl, founder and film critic at Smash Cut. I started Smash Cut in 2014 to share my love of movies and give a perspective I haven't yet seen represented. I'm also an editor at The New York Times, a Rotten Tomatoes-approved critic, and a member of the Online Film Critics Society.

Comments are closed.