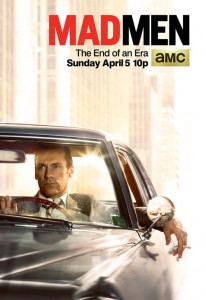

How will Don Draper die? Throughout the final episodes of Mad Men, which aired the second half of its final season this past spring, it was this question, and increasingly speculative answers to it, that dominated so much discussion of the show. As is so often the case with Mad Men, much of that speculation was beside the point. Like with previous similar speculation of the “Megan is surely Sharon Tate” variety, these questions treated Mad Men like a much more conventional, clichéd story than it has ever attempted to be. By the seventh season, you would think we'd know better. But no—we expected Mad Men to submit to conventional narrative tropes straight through to the very end.

This is likely why the conclusion that Matthew Weiner did provide was at first so jarring. Suddenly there are only ten minutes left of Mad Men, and Don Draper is in a share circle at a hippie commune, hugging a strange man and getting his om on. And then, “I'd Like to Buy the World a Coke.”

Weiner likely thought this ending fairly straightforward, and in fact it is. In the world of Mad Men, Don goes to the Mecca of enlightenment, reinvents himself once more, and subverts an entire subculture to sell soda—and he does it while creating arguably the most successful advertising campaign of the era. That there is any debate at all about this outcome is a testament to the complexity of the series, but that doesn't make the debate any less wrongheaded. Is it a cynical note to end the series on? Certainly. But it is also distinctly Mad Men, a fitting conclusion in its content and in its surface inscrutability.

Mad Men's final run is as notable for what it did not do as for what it did. It did not run through a laundry list of finale must-haves. (The one instance in which it did do this, with Stan and Peggy's rom-com moment in the finale, is one of the series' few bum notes.) It did not concern itself overly with explanation, or with tidiness. The finale does do more than it needs to set up “next acts” for the central characters, but this tidiness is happily subverted in many of the cases. Joan's business may fail. Pete and Trudy may be just as unhappy when they step off that plane. Roger may divorce again. Latter-day Mad Men devoted a lot of time to making its characters unbelievably materially happy; they all end the series millionaires. But if the millions didn't make them happy, there's no guarantee that a new job, a new boyfriend, a new try at marriage, or a new outlook on life will have any more success.

That's what makes the closing moments so great, and it's what means that they aren't, necessarily, as cynical as they appear on their face. That Don returns from his sojourn essentially unchanged is a truism of life, but it doesn't have to be a cynical one. That humans are fundamentally unchangeable is a core notion of the show. It would have been more cynical for Weiner to, in the eleventh hour, suddenly posit that the characters have finally bettered themselves—this time, it all works out! There is no magic salve for the human condition. We come as we are. Mad Men's thorough, nuanced, empathic understanding of this truth is its single greatest achievement, and that understanding is on display throughout this last set of episodes.

It's true of Betty, who, perhaps not entirely unexpectedly, receives the series' only truly tragic sendoff. Yes, Betty Francis ends the series with a cancer diagnosis, one that comes in the midst of her studies toward a psychology degree. But all the same traits are still there: the stubbornness that leads her to refuse Henry's insistence on more thorough care; the recklessness that leads her to, even briefly, consider a flirtation with a much older Glenn Bishop; and the hardness toward Sally that, ultimately, expresses itself as a kind of maternal protectiveness, in the lovely final letter that Betty pens to her daughter.

It's true of Peggy, who continues to climb the corporate ladder throughout this final run. For Peggy happiness is much more easily pinned down than it is for Don, but don't confuse that with contentedness. Peggy must always be moving; she, like Don, always has the next goal in sight. Part of it is that, for women, the goalposts are positioned rather differently. But part of it is that same hunger, and it's that hunger that scores her Bert's weird octopus painting, and it's that hunger that keeps her at McCann-Erickson, rather than running off to join Joan's business (which is not to belittle either option). It's that same hunger that makes her sudden realization of her love for Stan feel, if not wrong, then just a little too pat.

And it is, as always, true of Don. He ends the series where he began it, more or less. The penultimate episode finds him at a VFW hall, ever the outsider among these hardened veterans, who are nothing like Don. Secretly he thinks they are beneath him; they are the man he abandoned to become Don Draper. There is the creeping sense of dread, that perhaps Don will finally be found out, brought to task for his original sin—but no, that would be too obvious, and besides, we already knew, have known for some time, that the secret of Don's identity wouldn't matter. Bert shrugged it off, way back when. And it's not that identity that gets Don in trouble here. Instead it's his readiness to identify a kindred spirit, a ne'er-do-well teenager who cons the vets out of their money. Don tries to talk the kid off his path, and onto a better one, or at least, a different one than the path that Don chose. But people don't change. We come as we are.

The last set of episodes was more polarizing than perhaps would have been expected. Significant stretches of time were spent on seeming irrelevances; except that nothing is irrelevant in Mad Men's novelistic approach, should you be willing to take the time to engage it. The show concluded more vehemently denying its medium than ever—and it's a good thing. In doing so Matthew Weiner has delivered a stunning seven seasons' worth of consistently A+ drama. I am hard-pressed to think of a bad episode of Mad Men; I don't know that there is one. But don't be surprised when Mad Men goes home effectively empty-handed at this year's Emmys, too. There are sacrifices to be made in denying the medium, and among them are viewership and accolades. Those of us who invested the time, the thought, the energy, though—we know what we've experienced, and we know we're not likely to see anything of its kind again. Maybe that's hyperbole. Or, maybe, it's just advertising.

Standout episodes: “Time & Life,” “The Milk & Honey Route,” “Person to Person”

This paragraph is about the Emmys and how Mad Men should win, but probs won't.

Michael Wampler is a graduate of The College of New Jersey, where he completed both B.A. and M.A. degrees in English literature. He currently lives and works in Princeton, NJ while he shops around his debut novel and slowly picks away at his second. Favorite shows include Weeds, Lost, Hannibal and Mad Men (among many more). When not watching or writing about television, he enjoys reading, going for runs, and building his record collection.